Looking for leaders in all the wrong places

Tragic. This sums up my opinion on how most companies go about identifying candidates for leadership positions.

It’s not easy to predict who will be a high performer because isolating and evaluating an individual’s contribution for a successful outcomes is notoriously hard. Even if we believe their contribution was significant, there’s plenty of evidence that past performance is a poor predictor for future success.

So what is a good indicator of abilities and high potential?

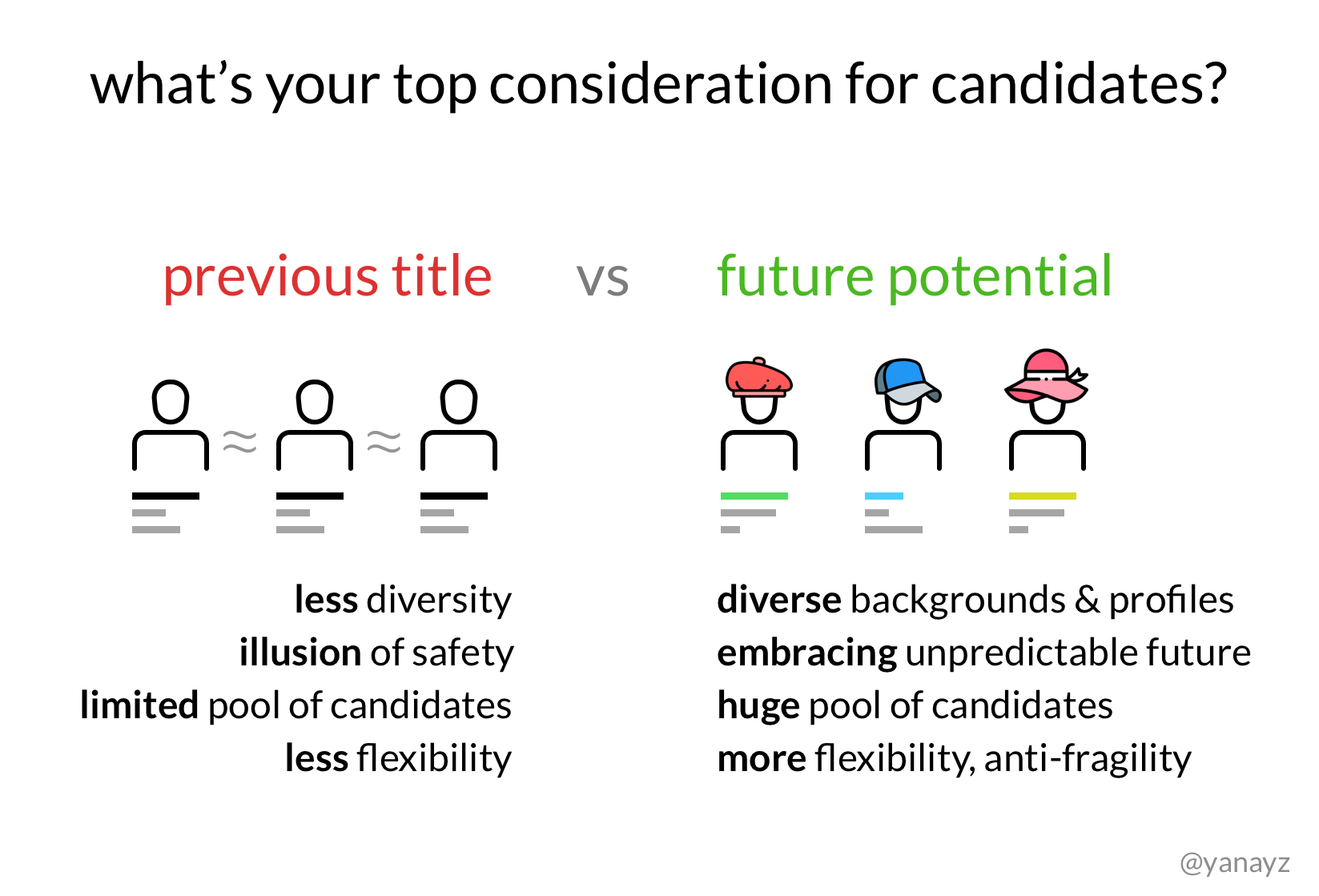

Looking at the most common practice in HR, the answer is simple: Their job title. If a candidate already holds the title we hire for, they automatically become a prime candidate. Extra points added if they worked for a bigger, more successful company.

This approach may seem reasonable, logical, even responsible.

Except it is deeply flawed and limited.

Let’s say you’re looking for a Head of Marketing.

How likely is it that by hiring someone who held this role at, say, airbnb, he’ll be able to reproduce their level of success? Slim. Very, very slim.

The reason is simple: the context is different, the timing is different, the product is (hopefully) different, but your expected outcome will remain the same.

By focusing on candidates with the “right” titles, you’re only more likely to end up with a less flexible employee. Someone who will feel attached to the way things were done before, and less likely to take risks that fit your unique context.

So why are we suckers for CV titles?

Because we want to make safe choices.

Even when the evidence is weak, the statistics are against us, and the opportunity cost is high. We are heavily biased towards safety.

And what feels safe?

More of the same, consistency, replication. It feeds our need for control.

But control is merely an illusion, and illusions hardly ever deliver great results.

The value of expertise

Here’s a pill that is hard to swallow for some: expertise in any subject matter (be it design, marketing, engineering, etc.) plays only a marginal role when it comes leadership positions.

How marginal?

Google for instance rank a manager’s technical knowledge as only the 8th out of 10 skills they look for. That’s the bottom 20%. How is that for marginal?

Depth of knowledge is useful, but you quickly reach diminishing returns when your main responsibility is leading others.

Leaders aren’t directly generating results. Their job is to inspire, influence and enable the people who can generate results.

What we should be looking for

Once we put fancy titles aside, we can start looking for the qualities that do matter:

- A wide perspective, resulting from diverse experiences and roles

- Strong interpersonal skills

- An ability to coach, drive, communicate, enable others

- A sense of urgency and optimism

- Low ego

Enough has been said about the last four, but I’d like to clarify the first one:

The more diverse your background and professional experience, the richer your insights will be.

As complexity of challenges increases, we desperately need to mix things up, to deliberately bring in fresh perspectives.

A curious, intelligent, and driven leader can have a dramatic effect, even if their understanding of the subject matter is basic. I’d even claim that their lack of expertise is a strength: they are much more likely to question boundaries, to deviate from accepted “wisdom”, to challenge what can be done, and how to go about it.

The outsider’s advantage

It’s the outsiders that often end up seeing what experts wouldn’t dare to consider.

There’s a lot of talk about diversity in organizations, but it’s usually the shallow version that refers to country of origin or skin tone.

Injecting diversity through less-obvious leadership choices (such as background in other domains) will not only shake up stale practices, but would also substantially increase the talent pool available for us, reducing the time it takes to fill in such positions.

Of course nothing can guarantee a successful integration or satisfactory performance, but if a candidate who meets the conditions above fails to meet our expectations, it’s more likely due to incompatibility on a personal level, or structural constrains within the organization, than their unorthodox CV.

A much needed recalibration

Fundamentally rethinking leadership candidate profiles isn’t nearly as risky as keep pretending that so-called safe choices deliver satisfactory results.

Finding great candidates will always be challenging, but if we focus on impactful skills instead of CV titles, realize the power outsiders can bring, and refuse to let fear drive our selection process - we’ll find that not only is the talent pool much larger than we imagined but also the potential of these candidates is significantly higher.